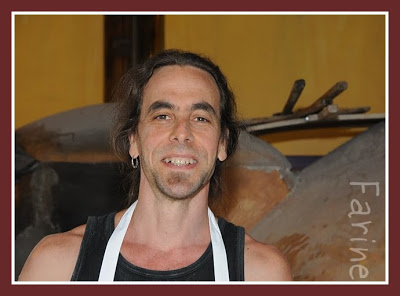

…or, rather meet the baker Jonathan Stevens and the fire-maker/minder, Cheryl Maffei, since they operate Hungry Ghost Bread in Northampton, Massachusetts, as a team.

Little did I know when we sampled that beet bear paw that we were actually eating a loaf made with local grains. “Locavorism” (is there such a word?) is big at the Hungry Ghost, so big that wheat is grown on a patch of land right in front of the bakery:

>

>

Hopefully grown-ups don’t have to be told where bread comes from but the wheat patch underlines the message that “amber waves of grain” need not be limited to Kansas, Montana or the Dakotas. Research has shown that wheat was grown in the Pioneer Valley (the name designates the three counties through which the Connecticut River flows in Massachusetts) as early as 1602 and a 95-year old friend of Jonathan’s whose parents owned a mill in North Amherst remembers local farmers bringing wheat, rye and corn to his family for milling.

After World War II, all grain production was centralized in the Western Plains where it could be done on a massive scale, free of pests such as blight. There was no perceived need to grow grain locally and as farm land became more and more valuable, farmers gave the preference to high-yield crops such as tobacco.

When they first started the bakery 10 years ago, Jonathan and Cheryl purchased their flour from a major flour distributor in a neighboring state. That distributor hasn’t operated a mill in a 100 years: it gets its grain on the commodity market and has it milled in North Carolina. Jonathan and Cheryl found it very difficult to reconcile their organic bread baking with such a huge carbon footprint. They wanted to bake from wheat grown locally or, at any rate, closer.

In March 2007, they put a call to farmers, saying that if they grew wheat, they’d buy it.

Leslie Cox, Manager of the Farm Center at Hampshire College (which, incidentally, is Jonathan’s alma mater) called to say that it wasn’t that simple. Cox, who comes from a family which has been growing wheat for generations in upstate New York, explained that there were 10,000 varieties of wheat, not all good for bread (his own family grew wheat mostly for pastry flour) . It is very wet in Massachusetts, which could be a problem, and the infrastructure needed to harvest, store and process the grain would be very expensive.

A meeting was organized at Hampshire College. Farmers were invited, as well as students and bakers. The outcome of the discussions was that the farmers would need a lot of help before any project could be launched. They needed to find out which varieties grew well in the Valley. A few were willing to experiment but there was no way around the fact that the infrastructure would be enormously expensive. Centrally milling the grain could cost up to one million dollars. What to do? Apply for federal funds? Resort to a massive fund-raising effort?

Maffei has a strong background in community organizing. She launched a grass-root appeal for volunteers to grow each 100 square feet of a specific variety. For more info, listen to this NPR radio program:

Over a hundred people (among whom many of their customers) responded. Coinciding as it did with the tripling of the wheat price in 2007, this renewed interest in local grains attracted the attention of CNN, the New York Times and MSNBC. The press coverage did a lot to promote the project and give it legitimacy.

Simultaneously Stevens and Maffei discovered La Meunerie milanaise, which gets most of its grain from Quebec farmers (it only purchases out West what cannot be grown locally). Quebec wasn’t the Valley but it was a lot closer than Montana and the example was electrifying: if wheat could be successfully grown in Quebec, then it could be done in Massachusetts. Together with the volunteers, they started growing the same varieties as the Quebec farmers, while working tirelessly to raise awareness about issues related to the commodity market and the need for a local supply of grain.

Word spread and more farmers started quietly to grow wheat (a great rotational crop in organic farming). At White Moon Farm in Easthampton, Carol and Ron Laurin grew seeds they got from a supplier. The following year, two more farmers (Lazy Acres and Plainville Farm in Hadley) agreed to try it in little patches. Out of the blue, Four Star Farm in Northfield (which used to grow turf for golf courses) planted 18 acres of pastry wheat, giving Jonathan and Cheryl the immense satisfaction of being finally able to use local flour in their crackers, cookies and other pastries.

But it wasn’t enough. Stevens – who, besides being a self-taught baker, is also a musician and a poet – and Maffei – who grew up in a large family in Boston and is passionate about food and cooking – wanted to grow more than the symbolic wheat patch in front of the bakery. They wanted to move the project forward by producing seeds themselves.

In June 2009, they attended the RENABIOS meeting in South-Western France. Renabios stands for “Renaissance de la biodiversité céréalière et du savoir-faire paysan” (Re-birth of cereals biodiversity and farmers’ traditional skills). The meeting was organized by the Réseau Semences paysannes (Farmers’ Seeds Network), created in 2003 to counter the tremendous loss of seed diversity and rusticity entailed by the agrobusiness model and to encourage the selection and multiplication of seeds at the farm level.

The Renabios meeting brought together farmers and artisans from 18 different countries, from Europe to the Middle-East, to share what they knew about the culture and uses of wheat and other cereals. (If you are interested in seeing pictures of that colorful event, I highly recommend browsing through Nathalie Bede’s gorgeous Renabios 09 album).

The Renabios farmers and artisans were also sharing ancient seeds, many of them actually not approved for cultivation in the European Union. Since the grain isn’t “legal”, they can’t sell the flour but they can use it to make bread and they sell that bread at farmers’ markets or in little shops. All of them are fiercely opposed to GMOs. Stevens and Maffei found the energy and dedication of these “paysans-boulangers” (farmers-bakers) well suited to the lone-wolf mentality that prevails in the Pioneer Valley of Western Massachusetts where farmers are struggling with the loss of the necessary infrastructure. Smaller used combines might be found to harvest the grain, the wheat might be milled in smaller mills which the farmers could operate themselves. Money might be procured under the Federal Farm bill through the value-added grant program.

Stevens and Maffei moved last month to a 26-acre farm in Montague, Ma, about 20-25 minutes from the bakery. Sloped but terraced, the land hasn’t been cultivated in 60 years. They will farm it in partnership with Rich Gallo, an apprentice organic farmer, and with the support of nearby professional farmers who have agreed to help with the equipment. The soil is beautiful, says Maffei. They will do two tillings, plant buckwheat in July, then in the fall sow ancient varieties of wheat (including Red Lama). After the harvest, the seeds will be distributed to farmers.

They will grow some clover for nitrogen and to cut down the weeds. In spring and summer, they will also grow a significant amount of herbs (including lots of basil to make pesto).

They are hoping the farm will also provide a space for the bread-making classes the community has been requesting for some years. In the beginning they’ll probably put in a small wood-oven but ideally they’d love a traveling oven which would enable them to reach other communities as well. The mixing will be done by hand since older varieties are more fragile and in any case the romance of hand-mixing appeals to aspiring bakers.

These new projects will take them away from the bakery for a few days each week but they now have a solid team of helpers who can manage operations when they are not around. Just as Stevens likes to stay in tune with the dough and doesn’t make exactly the same loaves from one batch to the next, he plans to remain attuned to the needs of the land and of the community and to shape his days accordingly. He sees variety as a form of personal renewal.

This passion for diversity is reflected in the bread schedule which provides pretty much for every taste. I was struck by the creativity with which Stevens conjugates the local loaf (bread made with local wheat): so far, besides the beet bear claw, I have tried the double wheat and the flatbread with coriander and each time I was astonished by the boldness of the flavors. I haven’t sampled all the breads yet but among those I have tried, I loved the olive fougasse and the semolina fennel and, for now, my absolute favorites remain the spelt loaf with chamomille and the French bâtard, both excellent. I was less impressed by the savory fold which featured so much thyme that it masked the taste of the other ingredients – white cheddar, sun-dried tomatoes, baby bella mushrooms and onion (in the interest of full disclosure, I must say that thyme is my least favorite herb, so maybe it was just me).

Stevens started as a home baker when he was a stay-at-home Dad. His first loaf was the pan bread from the Tassajara Bread Book, then he graduated to the country boule with starter and yeast. After his second son was born, he built an oven in the backyard. Then he bought a mixer and just extrapolated his knowledge. He sold his bread first to his sons’ friends’ parents, then to CSA’s. He attended Alan Scott’s gatherings out in Marin County, north of San Francisco, where nobody was an expert and knowledge-sharing was the rule. Peer education at its best! It enabled him to improve what he was doing. Later, he just learned from doing it over and over again. Stevens’ mantra today: pay attention and retard the dough. It makes all the difference…

For practical details such as address and business hours, please refer to the bakery’s excellent website where you’ll also find a trove of information regarding the back-to-local wheat movement, last year’s French experience , other rewiews, press coverage, etc. You’ll also discover the origin of the bakery’s lovely and mysterious name.

Lovely! I'd like to have my own patch of wheat… I should eliminate the lawn…

Great article and pictures, thank you.

Thanks MC for profiling another Artisan Baker with such a passion for his craft.

Oh wow, I'd be happy to meet them. I never really met a real baker. You are lucky!

I love that this bakery is family run. That's how you know it's quality stuff!

Dear MC,

I love your work. I think your "Meet the Baker" series of posts are full of "humility" (for want of a better word), and by that I mean, the human spirit which is so endearing and so lifting. Every single one of these bakers you write about, MC, is quietly going on about their honest work, like yourself.

Thank you so much for bringing these bakers to our attention. Without your writing about them, I wouldn't have known about the great human spirit manifested by them.

Shiao-Ping