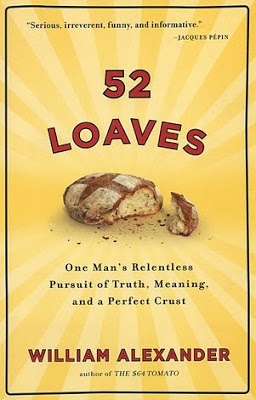

First book in a long time to make me me laugh out loud! William Alexander makes the quest for the perfect crust (crumb, actually, since he spends the better part of one year trying to get holes in his bread) sound both like the single-minded obsession of a slightly demented home baker (when he isn’t baking, Alexander is director of technology at a research institute) and a somewhat comical endeavor which ends up involving the whole family one way or another.

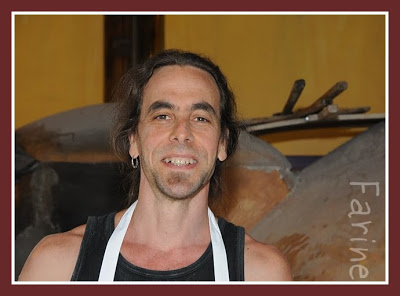

Meet the Baker: Jonathan Stevens

…or, rather meet the baker Jonathan Stevens and the fire-maker/minder, Cheryl Maffei, since they operate Hungry Ghost Bread in Northampton, Massachusetts, as a team.

Little did I know when we sampled that beet bear paw that we were actually eating a loaf made with local grains. “Locavorism” (is there such a word?) is big at the Hungry Ghost, so big that wheat is grown on a patch of land right in front of the bakery:

>

>

Hopefully grown-ups don’t have to be told where bread comes from but the wheat patch underlines the message that “amber waves of grain” need not be limited to Kansas, Montana or the Dakotas. Research has shown that wheat was grown in the Pioneer Valley (the name designates the three counties through which the Connecticut River flows in Massachusetts) as early as 1602 and a 95-year old friend of Jonathan’s whose parents owned a mill in North Amherst remembers local farmers bringing wheat, rye and corn to his family for milling.

After World War II, all grain production was centralized in the Western Plains where it could be done on a massive scale, free of pests such as blight. There was no perceived need to grow grain locally and as farm land became more and more valuable, farmers gave the preference to high-yield crops such as tobacco.

When they first started the bakery 10 years ago, Jonathan and Cheryl purchased their flour from a major flour distributor in a neighboring state. That distributor hasn’t operated a mill in a 100 years: it gets its grain on the commodity market and has it milled in North Carolina. Jonathan and Cheryl found it very difficult to reconcile their organic bread baking with such a huge carbon footprint. They wanted to bake from wheat grown locally or, at any rate, closer.

In March 2007, they put a call to farmers, saying that if they grew wheat, they’d buy it.

Leslie Cox, Manager of the Farm Center at Hampshire College (which, incidentally, is Jonathan’s alma mater) called to say that it wasn’t that simple. Cox, who comes from a family which has been growing wheat for generations in upstate New York, explained that there were 10,000 varieties of wheat, not all good for bread (his own family grew wheat mostly for pastry flour) . It is very wet in Massachusetts, which could be a problem, and the infrastructure needed to harvest, store and process the grain would be very expensive.

A meeting was organized at Hampshire College. Farmers were invited, as well as students and bakers. The outcome of the discussions was that the farmers would need a lot of help before any project could be launched. They needed to find out which varieties grew well in the Valley. A few were willing to experiment but there was no way around the fact that the infrastructure would be enormously expensive. Centrally milling the grain could cost up to one million dollars. What to do? Apply for federal funds? Resort to a massive fund-raising effort?

Maffei has a strong background in community organizing. She launched a grass-root appeal for volunteers to grow each 100 square feet of a specific variety. For more info, listen to this NPR radio program:

Over a hundred people (among whom many of their customers) responded. Coinciding as it did with the tripling of the wheat price in 2007, this renewed interest in local grains attracted the attention of CNN, the New York Times and MSNBC. The press coverage did a lot to promote the project and give it legitimacy.

Simultaneously Stevens and Maffei discovered La Meunerie milanaise, which gets most of its grain from Quebec farmers (it only purchases out West what cannot be grown locally). Quebec wasn’t the Valley but it was a lot closer than Montana and the example was electrifying: if wheat could be successfully grown in Quebec, then it could be done in Massachusetts. Together with the volunteers, they started growing the same varieties as the Quebec farmers, while working tirelessly to raise awareness about issues related to the commodity market and the need for a local supply of grain.

Word spread and more farmers started quietly to grow wheat (a great rotational crop in organic farming). At White Moon Farm in Easthampton, Carol and Ron Laurin grew seeds they got from a supplier. The following year, two more farmers (Lazy Acres and Plainville Farm in Hadley) agreed to try it in little patches. Out of the blue, Four Star Farm in Northfield (which used to grow turf for golf courses) planted 18 acres of pastry wheat, giving Jonathan and Cheryl the immense satisfaction of being finally able to use local flour in their crackers, cookies and other pastries.

But it wasn’t enough. Stevens – who, besides being a self-taught baker, is also a musician and a poet – and Maffei – who grew up in a large family in Boston and is passionate about food and cooking – wanted to grow more than the symbolic wheat patch in front of the bakery. They wanted to move the project forward by producing seeds themselves.

In June 2009, they attended the RENABIOS meeting in South-Western France. Renabios stands for “Renaissance de la biodiversité céréalière et du savoir-faire paysan” (Re-birth of cereals biodiversity and farmers’ traditional skills). The meeting was organized by the Réseau Semences paysannes (Farmers’ Seeds Network), created in 2003 to counter the tremendous loss of seed diversity and rusticity entailed by the agrobusiness model and to encourage the selection and multiplication of seeds at the farm level.

The Renabios meeting brought together farmers and artisans from 18 different countries, from Europe to the Middle-East, to share what they knew about the culture and uses of wheat and other cereals. (If you are interested in seeing pictures of that colorful event, I highly recommend browsing through Nathalie Bede’s gorgeous Renabios 09 album).

The Renabios farmers and artisans were also sharing ancient seeds, many of them actually not approved for cultivation in the European Union. Since the grain isn’t “legal”, they can’t sell the flour but they can use it to make bread and they sell that bread at farmers’ markets or in little shops. All of them are fiercely opposed to GMOs. Stevens and Maffei found the energy and dedication of these “paysans-boulangers” (farmers-bakers) well suited to the lone-wolf mentality that prevails in the Pioneer Valley of Western Massachusetts where farmers are struggling with the loss of the necessary infrastructure. Smaller used combines might be found to harvest the grain, the wheat might be milled in smaller mills which the farmers could operate themselves. Money might be procured under the Federal Farm bill through the value-added grant program.

Stevens and Maffei moved last month to a 26-acre farm in Montague, Ma, about 20-25 minutes from the bakery. Sloped but terraced, the land hasn’t been cultivated in 60 years. They will farm it in partnership with Rich Gallo, an apprentice organic farmer, and with the support of nearby professional farmers who have agreed to help with the equipment. The soil is beautiful, says Maffei. They will do two tillings, plant buckwheat in July, then in the fall sow ancient varieties of wheat (including Red Lama). After the harvest, the seeds will be distributed to farmers.

They will grow some clover for nitrogen and to cut down the weeds. In spring and summer, they will also grow a significant amount of herbs (including lots of basil to make pesto).

They are hoping the farm will also provide a space for the bread-making classes the community has been requesting for some years. In the beginning they’ll probably put in a small wood-oven but ideally they’d love a traveling oven which would enable them to reach other communities as well. The mixing will be done by hand since older varieties are more fragile and in any case the romance of hand-mixing appeals to aspiring bakers.

These new projects will take them away from the bakery for a few days each week but they now have a solid team of helpers who can manage operations when they are not around. Just as Stevens likes to stay in tune with the dough and doesn’t make exactly the same loaves from one batch to the next, he plans to remain attuned to the needs of the land and of the community and to shape his days accordingly. He sees variety as a form of personal renewal.

This passion for diversity is reflected in the bread schedule which provides pretty much for every taste. I was struck by the creativity with which Stevens conjugates the local loaf (bread made with local wheat): so far, besides the beet bear claw, I have tried the double wheat and the flatbread with coriander and each time I was astonished by the boldness of the flavors. I haven’t sampled all the breads yet but among those I have tried, I loved the olive fougasse and the semolina fennel and, for now, my absolute favorites remain the spelt loaf with chamomille and the French bâtard, both excellent. I was less impressed by the savory fold which featured so much thyme that it masked the taste of the other ingredients – white cheddar, sun-dried tomatoes, baby bella mushrooms and onion (in the interest of full disclosure, I must say that thyme is my least favorite herb, so maybe it was just me).

Stevens started as a home baker when he was a stay-at-home Dad. His first loaf was the pan bread from the Tassajara Bread Book, then he graduated to the country boule with starter and yeast. After his second son was born, he built an oven in the backyard. Then he bought a mixer and just extrapolated his knowledge. He sold his bread first to his sons’ friends’ parents, then to CSA’s. He attended Alan Scott’s gatherings out in Marin County, north of San Francisco, where nobody was an expert and knowledge-sharing was the rule. Peer education at its best! It enabled him to improve what he was doing. Later, he just learned from doing it over and over again. Stevens’ mantra today: pay attention and retard the dough. It makes all the difference…

For practical details such as address and business hours, please refer to the bakery’s excellent website where you’ll also find a trove of information regarding the back-to-local wheat movement, last year’s French experience , other rewiews, press coverage, etc. You’ll also discover the origin of the bakery’s lovely and mysterious name.

JT’s 85×3

This bread with an improbable name is the one which won its creator John Tredgold (aka JT) a spot on Bread Team USA 2010, so you’d better believe it’s good. It is in fact awesome, so much so that it will become a fixture in my house on baking days. You should have seen the speed at which it was wolfed down by my grandchildren when I brought the loaves over. Everyone went back for seconds and thirds, from the 3-year old twins to their teenage brother and sister. Of course the older kids were completely unaware when devouring it that they were ingesting the very same healthful whole grains as the ones they scorn when listed on the wrapper of a supermarket sliced loaf. Nothing like a deliciously crunchy crust and a complex taste to make you forget your dearest principles!

The 85×3 gets its matchless aromas from a high-extraction flour as well as from the use of three different preferments, a biga, a poolish and a levain. The biga and the levain are made with 100% high-extraction flour while the poolish uses regular bread flour.

JT used Artisan Old Country Organic Type 85 malted Wheat Flour (ash content: 0.85%) from Central Milling. I didn’t have access to that flour, so I used La Milanaise‘s “farine tamisée” which contains just a tad more bran. La Milanaise flours are not sold retail in this country. I got mine from a friend who owns a bakery. If you don’t have access to a high-extraction flour, a reasonable substitute would be to use 80% organic white flour and 20% whole wheat flour.

I didn’t have raw wheat germ, so I left it out of the recipe. Also because it was cool in my house (much cooler than in the bakery at Semifreddi’s), the poolish and the biga took their own sweet time to ferment and I ended up mixing the final dough too late in the day to contemplate baking before night. So I left the dough at room temperature (about 64 F/18C) for one hour, folded it once and put it in the fridge (on the top shelf where it is a tad less cold). The following morning, I took it out, gave it a fold and let it come back to room temperature (one hour and a half to two hours) before dividing, shaping, etc.

JT’s original formula can be be found here. The recipe below is my interpretation.

Ingredients: (for 2 bâtards, 1 fendu, 2 crowns and 1 boule)

190 g high-extraction flour

114 g water

0.003 g salt (a tiny tiny pinch, basically a few grains)

0.003 g instant yeast (a tiny tiny pinch too)

Poolish

190 g organic white flour

209 g water

0.003 g salt

0.003 g instant yeast

Levain (mine was 40% whole-grain, mostly wheat and spelt with a little bit of rye)

380 g high-extraction flour

209 g water

190 g firm starter

Final dough

631 g high-extraction flour

353 g organic white flour

761 g water (I used slightly less water than JT, probably because my flours were less thirsty than the ones he used)

34 g salt

0.17 g instant yeast

305 g biga

400 g poolish

780 g levain

Method (this bread is made over two days)

- Mix the biga, the poolish and the levain and leave them to ferment at room temperature for 10 to 12 hours

- When the preferments are ready, mix flour, poolish and 80% of the water in the bowl of the mixer until the flour is completely hydrated and let rest for 30 minutes (autolyse)

- Add the biga, the levain, the yeast, the salt and remaining wateras needed and mix until the dough starts to develop strength, then add more water until medium soft consistency is reached (JT says: “A second water addition is used for this mix. I tend to prefer this style of mixing. Instead of holding back say 5-10% of the water and dribbling it into the bowl when you feel comfortable. I like to create the final dough and on the last minute throw all the water in one go. The dough will start to shred and start ‘swimming’. Do not panic and add flour! It’s a bit like accelerating through a skid, Don’t put your foot on the brake”)

- Transfer the dough to an oiled container, cover it tightly

- Give it a fold after one hour then put the container in the fridge overnight

- In the morning, take the dough out of the fridge and give it a fold

- Let it come back to low room temperature and divide by 500 g, preshaping as cylinders or boules according to the desired shapes

- Shape and let proof, covered, for one to one and a half hour

- Pre-heat the oven to 470 F/243 C one hour before baking (my oven doesn’t heat very well. A lower temperature setting might work just fine in your oven), taking care to put it in a baking stone and, underneath, a heavy metal pan for steaming (mine contains barbecue stones which we bought solely for steaming purposes)

- Dust with flour and score as desired (as can be seen from the above pictures, deep scoring and angled surface scoring yield very different “ears” in the final loaves)

- Pour a cup of water over the barbecue stones in the steam tray, lower the oven temperature to 450 F/232 C and bake for 40 minutes

- JT recommends turning off the heat after 30 minutes and leaving the bread an additional 15 minutes in the oven with the door ajar. I will try that next time as I found the crumb a little bit moist when I first sliced open one of the cooled loaves.

JT’s 85×3 goes to Susan, from Wild Yeast for Yeastpotting.

Meet the Baker: John Tredgold

At first glance, John Tredgold, who prefers to be called JT, may seem an unlikely candidate for an artisan profile on this blog since he is Director of Bakery Operations at Semifreddi’s, a large Bay Area bakery which is justifiably proud of its “handcrafted bread & pastries” but makes no claim whatsoever to artisan baking.

The truth is however that JT leads a double life and that, in his other life, he is one of nine artisan bakers selected in 2009 to train for the North American Louis Lesaffre Cup competition which will take place in Las Vegas this coming September.

Together these nine bakers form the Bread Bakers Guild Team USA 2010. Each of them specializes in one of three categories: Baguette & Specialty Breads, Viennoiserie and Artistic Design. JT is a member of the Baguette & Specialty Breads sub-team.

If the US wins the Lesaffre Cup, then it also wins the right to compete in the Coupe du monde de la boulangerie (Bread World Cup), an event that it is to the world of baking what the Olympics are to the world of sport. There is no guarantee that the present members of Team USA 2010 will be chosen to represent the US in Paris. However they might be.

So JT has a fighting chance to follow in the tracks of the legendary US artisan bakers who, in 1996, won first place in the baguette and specialty breads competition, upsetting the French, and took the gold both in 1999 and in 2005!

Now, how do you get from a semi-industrial bakery in Alameda, California, to a spot on Team USA? Well, it is a long story, one which begins in the United Kingdom in the 80’s when JT, then aged 14 and a British citizen, started working in a bakery. Bread was pretty awful in the UK at the time however: “bland” was probably the kindest adjective that could be used to describe it. There were no real possibilities for apprenticeship.

So, in his late teens, JT decided to try his luck on the other side of the Atlantic. He first found work decorating Baskin-Robbins cakes at a New England mall. Although he did enjoy the job, he quickly moved on. After a few return trips to England, 1993 found him on the West Coast where a Help Wanted ad in a local paper pointed him towards Semifreddi’s, a much smaller operation then than today. JT was hired as a shaper, a job for which his British work experience had prepared him well .

JT shaped breads for one year. But he wanted to work the deck and rack ovens. He wanted to supervise a crew. So he kept pushing and learning and climbing up the ladder and eventually, in 2000, he was offered the job of Director of Bakery Operations when it became available.

Semifreddi’s was then struggling with expansion and quality. Some things were not being done exactly right on the production floor but it was difficult for JT to pinpoint which ones. So he registered for the Artisan I workshop at SFBI and after taking the class and talking things over with Michel Suas and other instructors, he was able to convince Semifreddi’s owners to invest some time and money and implement a few changes.

Today the company makes 35 different products and a dozen pastries daily. Every day, there are problems to solve: training issues, lack of focus, lack of understanding. JT’s job is to make sure production happens. Although production baking has very little to do with new formulas, he never loses track of his artisan training and always tries to push knowledge in the production line, striving to show that if a slightly different approach were to be implemented, then the product would improve. All the managers are required to attend one training session at SFBI every year (paid for by the company), so the knowledge base is much stronger today among the bakery operators.

By 2002, JT was managing the bakery but sorely missed having his hands in the dough. He was among the spectators who saw Japan win the gold at the Bread World Cup while the US came silver. More than anything, he wanted to be part of the team. So, the following year, he went back to SFBI where Didier Rosada – the US Team coach – was an instructor and asked him if he would watch him make three breads and tell him whether or not he had a chance. Didier watched. JT wasn’t ready.

Back in Paris in 2005 to attend the competition again, he witnessed the stunning US victory and came back more determined than ever to make it to the World Cup but life intervened and he wasn’t in Paris in 2008, not as a team member nor even as a spectator, to see the United States lose to France, Taiwan and Italy by a fraction of a point, securing a 4th spot but no medal.

With more experience and training under his belt, JT decided in 2009 that he was ready and he registered for the Draft for Team USA 2010. The audition process for the team took the shape of regional workshops during which Team USA alumni judged the candidates’ skill, adaptability and teamwork. For JT and other candidates in the Western US, the workshop took place at the California Culinary Academy in downtown San Francisco, California.

Each candidate was required to bring six formulas in Excel format with baker’s percents, one of which he or she would be requested to bake from. They were allowed to bring their own levain. Each audition workshop was three-day long.

On the first day (a half-day), the candidates were split into groups and asked to prepare preferments for the day after. JT was asked to make a 100% whole wheat basic loaf, a basic baguette (with poolish) and a basic rye bread (with medium rye flour). The candidates were told they could change the formulas if they liked. They had 30 minutes to prepare before starting.

On the second day, the teams were asked to mix, shape and bake. JT says: “It was pretty stressful, not only because of the pressure but because you didn’t know your partner. A lot of important decisions had to be made as to the mixing (in JT’s opinion, more than flour and temperature, it is when you choose to stop mixing that influences the bread), the amount of water to use, the length of the fermentation (JT favors a long one, adjusting the temperatures accordingly afterwards) and the baking , and you didn’t know whether you could trust your partner’s instincts. Also all the mixers were Hobarts, there was no retarder and you had to make do with a lone electric deck oven which didn’t function properly (a few of the decks had no steam). It became clear that the judges were looking for how you would behave, accept responsibility and errors, etc. Could you handle things when they start to go wrong?”

At the end of the second day, each candidate was told which of his or her own formulas he or she would have to bake the following day. In JT’s case, the judges picked the 85×3, an aromatic country wheat bread made with 0.85% ash flour and three different preferments. Another candidate made a beer bread, another yet an olive bread. Some had submitted formulas with strongly flavored ingredients and JT remembers wondering if the flavors would be overpowering, preventing the judges from distinguishing the grain’s aromas. Each formula had to be baked in three different shapes.

JT mixed his dough and once mixing was over, he felt a little more relaxed, knowing that he was on the right course and that the bread would say what he wanted it to say, despite the challenges with the oven. When it was time to bake, he was in full production managing mode, staggering and organizing oven times so that each candidate could start his or her bread in a properly steamed oven, switching to a no-steam deck as soon as maximum oven rise was reached.

At the end of the day, the instructors evaluated the products and provided a critique. They based their final decision on the technique, work habits, attitude and creativity of each candidate but also of course on the quality and taste of the final product.

The draft workshop which JT attended took place in May but he didn’t learn until October that he had made the team (the results of all regional workshops had to be in before the judges could make a decision).

Now that JT is on Team USA 2010, he needs to practice, practice, practice. As it is not always easy for the candidates to find time to train during the workday, training sessions are organized, which all candidates are required to attend.

The first one, Baguette Practice, took place on the last weekend of February in San Francisco. Already back East by then, I sent JT an email to find out how it went. His reply left me gasping for air: “It was sink or swim. I had never done anything like this before. Mike & Roger were calm and relaxed, I felt good. Planning & timing became key components immediately. No time to waste , no time to spare, everything fluid & precise, 200Kg batches of dough are more forgiving than 5kg. My first dough was too wet, make a decision, move on. Second dough better, elastic, good temp. Next step. Never panic & never give up. 8 ½ hours later, the first practice was done…” Wow! Did he stop to breathe when he wrote that, not to mention during the whole practice session?

JT told me that bread was constantly on his mind: “Everything is mental, you know. I practice in my head a lot. I think about what I did, where I placed my hands. Did it make a difference? Did I do this or that because every one else was doing it or because the dough needed it? It is essential to learn how to read the bread and the dough. So, in my head, I run a virtual practice session all the time.”

In many ways, JT’s passion for bread reminds me of Gérard. For both, the only bread that matters is the one leavened with levain. Both are at the same time totally committed and totally zen in their relationship with the dough. Both believe that less is more, that the dough must be handled as little as possible. Both are bakers, first and foremost. Eveything else in their lives gravitates around that.

As JT believes that his 85×3 (click on the link to see the formula) helped win him a spot on Team USA 2010, he decided to bake it for Farine readers and have me taste it. At first bite, I loved the crust and crumb textures but I wasn’t sure I could taste all the aromas. But then I let it rest overnight and boy, had it improved! At 8:00 AM the following day, it was delicious. At 11:00, it was truly fantastic, in the same league as Gérard‘s bâtard or Vatinet‘s baguette. Same thing happened when I tried the formula at home: it was excellent the first day and it kept getting even better as the hours passed.

I wonder if this has to do with the fact that the crumb seems a bit moist when one first slice through a loaf. The flavors become more apparent when it dries up a bit. JT turns off the oven after 30 minutes and leaves the bread another 15 minutes in the oven with the door open. I forgot to do it but I’ll give it a try next time.

JT was kind enough to allow me to shoot videoclips as he worked. So if you are curious to see a champ at work, by all means take a look!

Best Baguette Prize 2010 awarded in Paris…

…and the winner is Djibril Bodian from Le Grenier à pain – Abbesses. Check out this post on In Transit, the New York Times travel blog.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 52

- 53

- 54

- 55

- 56

- …

- 76

- Next Page »